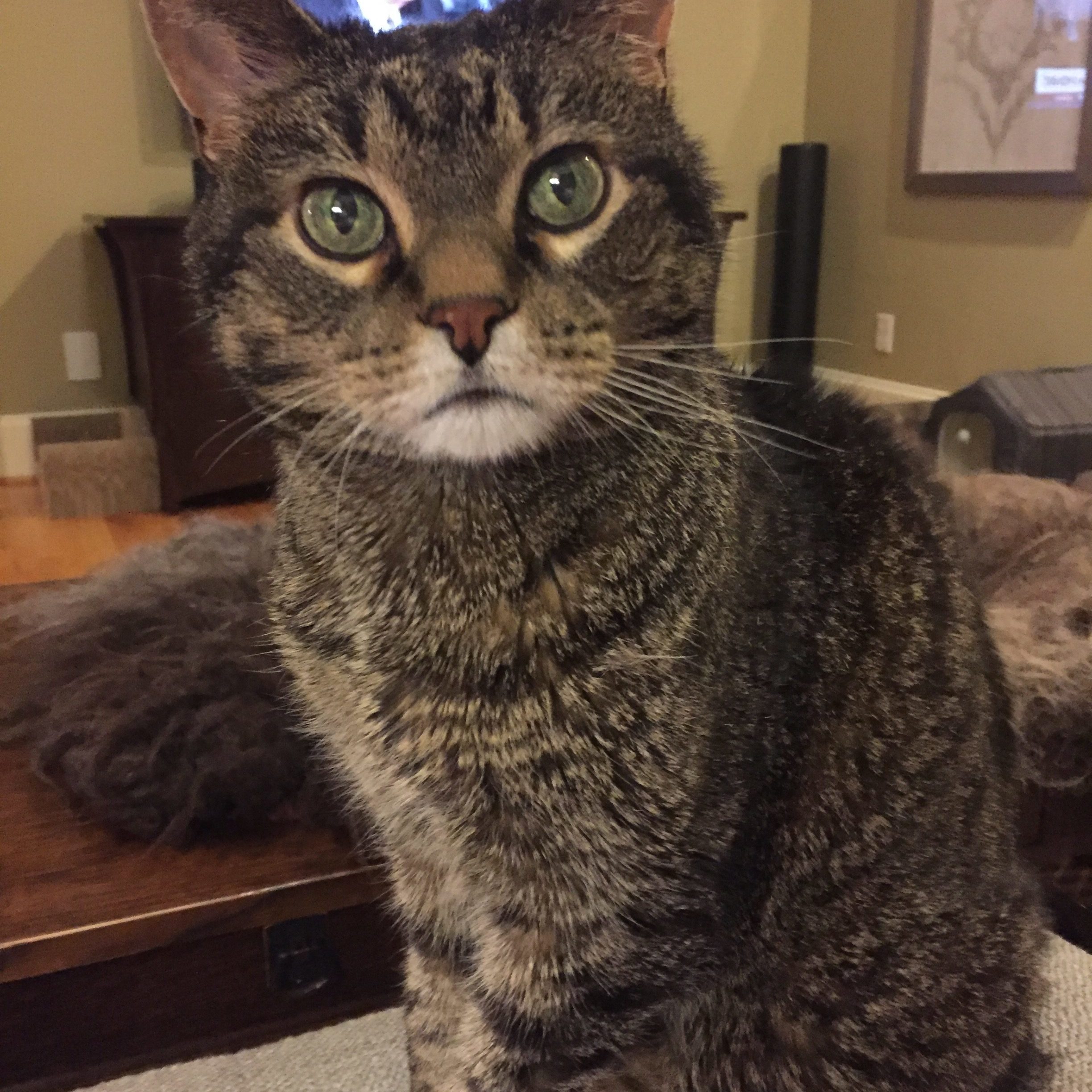

My cat Jake is old, deaf, and fully retired. I come at him three times a day with medication, and as long as he’s pain-free and using the litter box, I don’t mind being his home healthcare nurse. This arrangement could go on for years if you ask me. I’m happy he is still around.

But, in reality, it won’t go on for years. Jake is in the fourth quarter of his life, and there are nights when I have to poke him with a feather-on-a-stick him to make sure he’s sleeping and not dead.

The other morning, I couldn’t find Jake in any of his cat beds or hideyholes. I searched all over the house, and I started to freak out. But I stopped myself from panicking and said to my husband, “I’m going back to the basement. I’m sure Jake is down there. If I find his body, I won’t scream. I will call your name, though.”

That action — of thinking through my shitty scenario and trying not to lose it — is the culmination of a lot of hard work towards managing my stress. And it’s also the extension of work I’m doing to become more resilient.

Quite simply, I know that whatever is out there, no matter how terrible, I can handle it. I don’t need someone to help me contain my fear, rage or grief; I don’t have to drag everyone down with me when I’m feeling toxic, troubled or anxious. I can be my own container.

Being resilient and containing my stress and emotion is a ton of work, and it’s a deliberate practice that I have to visit every day. I’m learning how to manage the small stuff to build up some muscle memory for when life takes an unexpectedly terrible turn.

Like finding my dead cat’s body. When that happens, it will suck.

But, as it turns out, Jake isn’t dead just yet. He’s still sneaky and quick enough to hide when I’m coming at him with his medications. And it’s adorable when he tries to outrun me and get away. I like his confidence.

So, thankfully, I still have some time to work on being my own container and being more resilient. I also still have more time with Jake, knock on wood. That’s what matters most.

Our oldest Sheltie is around 16-17 years old. He’s mostly deaf and blind, has arthritis and possibly the beginning of dementia, and sleeps for around 20 hours out of 24. He’s still excited at every mealtime and to go for his very short and slow (about 100-foot) walk daily. So his quality of life is still pretty good for an extremely senior dog.

We’re glad he’s still here, as are his other three younger Sheltie packmates. We sometimes watch him sleeping to make sure he’s still breathing, but so far he always is. But we also know the day we dread will come. And that’s okay.

We’ve been here before and will be again. It’s hard to see them go, and even harder to have to help them along when they are suffering with no hope of relief or recovery.

We know we have given our rescued Shelties the best lives we can, as well as our hearts. Just like you have to your cats, Laurie. And that’s enough.

HI, Great post. Being resilient, not only in our work life but also personal life, matters a lot.

Your personal life reflects on your work life.

You have given the example of finding a much loved cat and the anxiety and stress that follows it. It was good.

We need to feel our emotions and observe them as an external person. When we do this, there is stillness and answers will come through. Being positive of the situation no matter what happens is very difficult.

I agree with you on your other posts as well. We need to train our mind and it takes a lot of hard work and many years.

Nice post. Great insight. Enjoyed reading it. Thank you. Cheers, Ramkumar